Author: Joel Farley, Ph.D.

As insurers, employers, governments, and others who pay for health care demand greater value for their money, evaluating “value” has taken on much greater importance. “Value” includes elements of quality and cost. Quality improvement has been a driving force for innovation in health care for decades. Better treatments, better tools, and better techniques have helped to extend life and improve the quality of life. Managing cost has always been a concern, but has taken on much greater importance as healthcare spending continues to grow and comprise nearly 18 percent of our overall economy.

To ensure that doctors, hospitals, and other providers are focused on value, those paying the bills are tying how much those providers get paid for delivering care to the quality of care they provide and at what cost. These pay-for-value efforts aimed at physicians and hospitals are common in today’s health care. Pharmacists, however, are rarely the direct subjects of a pay-for-value effort. That is changing through groundbreaking research underway in North Carolina.

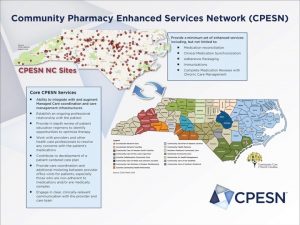

Joel Farley, a Professor in the UNC Chapel Hill Eshelman School of Pharmacy, is working with Community Care of North Carolina to help implement a large-scale, pay-for-value research project involving the North Carolina Community Pharmacy Enhanced Services Network (CPESN), a network of 250 community pharmacies across the state of North Carolina providing enhanced pharmacy services to patients.

The research effort compares the performance of CPESN pharmacies to pharmacies outside the CPESN program and pay pharmacists for health care improvements in their Medicare and Medicaid populations. Those improvements are measured as patient-centered outcomes including reduced hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and lower total costs of care. Those delivering improved outcomes will be paid more on a per member per month basis. Those not improving outcomes are paid less.

The research effort compares the performance of CPESN pharmacies to pharmacies outside the CPESN program and pay pharmacists for health care improvements in their Medicare and Medicaid populations. Those improvements are measured as patient-centered outcomes including reduced hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and lower total costs of care. Those delivering improved outcomes will be paid more on a per member per month basis. Those not improving outcomes are paid less.

Focusing on medication management and community pharmacy to help drive health improvements makes sense. After all, most people who see a physician leave that office visit with at least one prescription and, often, more than one. Research shows that appropriate medication use and adherence can reduce costly complications that otherwise lead to avoidable hospitalizations, ED visits, and doctors’ visits, and even premature death. Also, community pharmacies are available and accessible in communities across the country at convenient hours seven days a week. Optimizing the benefits of medication use through community pharmacy interventions accordingly has the potential to improve health dramatically and lower the preventable utilization of other, often more expensive health care services.

Though perhaps simple in concept – pay more for better outcomes and less for poorer outcomes – pay-for-value efforts in health care are much more complicated to implement than may appear, particularly when it comes to defining and measuring quality. In health care, quality measures generally fall into three different categories:

- Structural: Are the equipment and tools in place to deliver a successful outcome?

- Process: Are the appropriate steps taken to deliver a successful outcome?

- Outcome: Is a successful outcome achieved?

Dr. Farley describes an example of how these outcomes can be used to measure quality by illustrating the quality of a trip using car service Uber. The quality of an Uber ride might be influenced by the type of car you travel in, which would be an example of a structural measure of quality. In general, a ride in an old, dented car that has not been serviced in several years would be a lower quality ride than traveling in a new luxury vehicle. The adherence of the Uber driver to the rules of the road on your trip would be an example of a process measure. If the driver obeyed the speed, used his turn signal, and was courteous of other drivers during your trip, that would be a higher quality trip than someone that did not obey these rules. Finally, instead of measuring the tools or processes available to the Uber driver, one might rate the quality of the trip on the final outcome. Did the driver get you to your destination safely and on time?

Similar measurements of pharmacy performance can be drawn from this example. The availability of particular resources at a pharmacy is an example of structural measures that might reflect higher quality of care. Following practice quidelines proven to result in higher quality care is an example of process measures to evaluate pharmacy services quality. Finally, pharmacists can be measured on patient health-related outcomes. Those outcomes might include preventing the need for hospitalization or emergency department (ED) visits, improved patient adherence to medications, or the impact on the total cost of healthcare spending on their patients. Outcomes are ultimately the measures that are important to patients and payers.

Outcomes matter, particularly with health care. To most, a quality result from a medical intervention would be that the patient is better in terms of clinical markers of health improvement, overall well-being and functioning, or ideally both. Measuring those outcomes and determining who caused them can be a challenge, however. Many, many factors influence health – decisions within the medical system and outside of it, actions within the control of a single clinician and those made by multiple providers, and still more firmly in the control of the patient. Was it one particular action that made the difference or was it a concert of actions that did it? Determining what is making a positive difference is critically important to helping others replicate successful quality improvement and delivering greater value.

In addition to assisting with the implementation of this new innovative payment model, Dr. Farley and other researchers at the Eshelman School of Pharmacy’s Center for Medication Optimization through Practice and Policy are busy evaluating the effect of the program. Results of this project are forthcoming and preliminary estimates suggest that the program does help certain groups of patients improve outcomes.

The pay-for-value movement in health care is here to stay and all those with an impact of health outcomes have a role to play in their improvement. Optimizing medication use holds tremendous potential in both improving health outcomes and avoiding the medical urgencies that can lead to expensive ED visits and preventable hospitalizations. This research is evaluating the difference community pharmacists can make in driving better health outcomes and is informing the future of pharmacy practice and health care delivery overall.

Funding Opportunity Notice: The project described was supported by Grant Number 1C1CMS331338 from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

General Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies.”

Research Disclaimer: “The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented here was conducted by the awardee. Findings might or might not be consistent with or confirmed by the findings of the independent evaluation contractor.